Using Fermented Food To Reset The Gut Microbiome

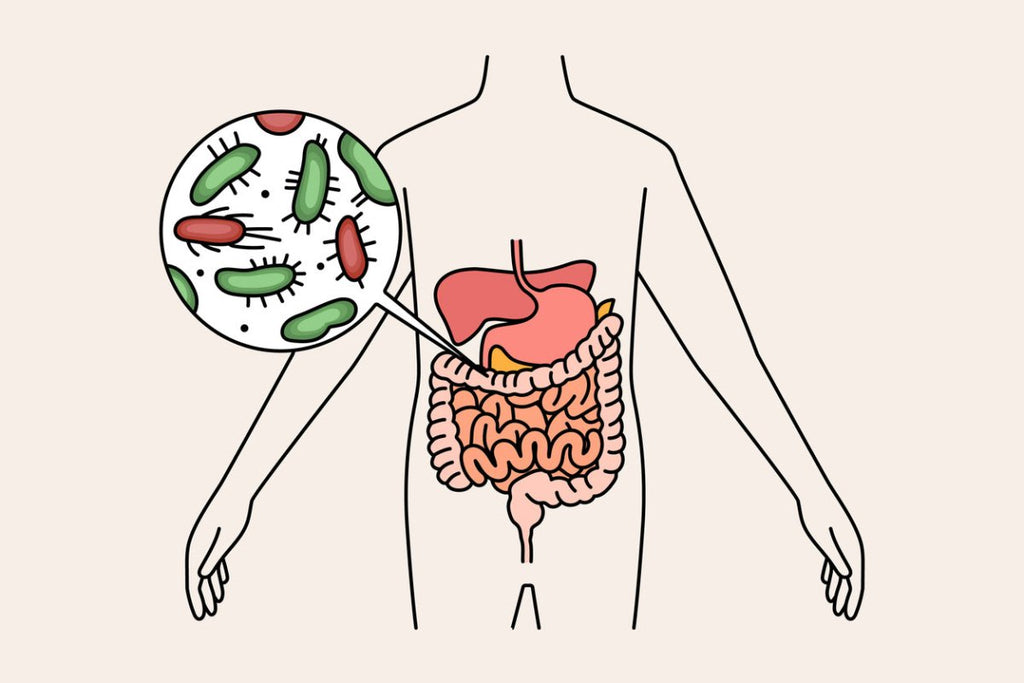

Fasting and fermented foods have become two of the most popular trends in health, food, and wellness over the last few years. We say “trends” but in fact, both have been with us for thousands of years. Throughout history, societies have dealt with famine. This has meant extended fasting as well as intermittent fasting. Particularly in agrarian communities, enforced periods without food has been the result of the failure of crops due to disease or pestilence, as well as the inability to grow crops in the colder months. This is particularly so in the cooler parts of the world. Fasting by choice has also played a key role in many religions of the world. The link between fasting and fermented foods is also clear. Fermented foods such as sauerkraut and kimchi were originally produced to store food in the cooler months, to provide sustenance in winter. But are they linked in another way? Can fermented foods help to repopulate the gut with beneficial bacteria after long-term fasting? We hope to find out more in this two-part series. In the first part, we’ll look at what intermittent and longer-term fasting are and how it relates to the gut microbiome. In the second, we’ll examine how re-populating the gut with fermented foods such as sauerkraut is the best way to repopulate the gut with beneficial bacteria when the fast is over. Intermittent fasting Very much in vogue, supporters of intermittent fasting have claimed its many health benefits. This includes weight loss, boosting longevity, strengthening your gut and improving mental health. There are many types of intermittent fasting. Most are usually described according to the calorific restriction and the time this is reduced. For example, is referred to as the 16/8 diet. This means the person on the diet fasts for 16 hours and takes their meals during a selected eight-hour period. There are also alternative day fasts, the more restrictive 20/4 diet and many more. A Harvard University health article suggests the timing of the intermittent fasting schedule is crucial. But what does the science say? While reports are inconclusive, and more research is needed, there is some tentative scientific backing for these claims. The Food and Mood Centre, part of Deakin University is currently conducting a study that will investigate the link between intermittent fasting and Chronic Heart Failure (CHF). According to the Centre, animal studies have shown a reversal of damage caused by heart disease. “In rat models of CHF, 6 weeks of IF on alternate days reduced body weight and successfully reversed cardiovascular damage. Relative risk of death was reduced by 84%,” it said in an article on the centre’s website. The new research is designed to examine whether intermittent fasting can be good for the health of humans. Much of the interest in research on intermittent fasting has been on whether it can help us lose weight, one of the fundamental health problems of our time. A 2021 study on mice by the University of Sydney, found that while belly fat undergoes “...dramatic changes during intermittent fasting”, some visceral fat becomes resistant to intermittent diets. “This suggests the visceral fat can adapt to repeated fasting bouts and protect its energy store,” said Dr Mark Larance from the university’s Charles Perkins Centre. “This type of adaptation may be the reason why visceral fat can be resistant to weight loss after long periods of dieting.” Longer-term fasting and gut health This has been with us for centuries, with longer-term fasting often described as abstinence or doing without much (or any) food for a specific period. Examples of such prolonged fasting are usually seen in religious contexts — used as ritual abstinence — or for more long-term health goals. However, studies in mice have also shown prolonged fasting may cause some changes in gut microbiota. As the digestive tract is used less, it may remodel the gut’s structure, according to studies. But what of gut health? Does fasting boost the friendly gut microbes in any significant way? Next week we’ll take a closer look at the effects of, particularly, longer-term fasting on gut health. We’ll examine how repopulating the gut with fermented foods such as sauerkraut may be one of the quickest ways to restore balance in the gut microbiome. Join us next week when we go into the restructuring of the gut during prolonged fasts in more detail. We’ll also look at the role eating fermented foods, such as sauerkraut, helps re-populate the gut when the fast is over. As always, we at Gutsy Ferments recommend you consult your health and nutrition professional before starting any diet.

Browse Our Blogs

Unlock the Fermented Power: How Kimchi Can Supercharge Your Gut Health and Beyond

If you've ever cracked open a jar of kimchi and been hit with that tangy,...

Read More

The Benefits of Fermented Foods for Your Gut Health

Looking after your gut health is an important part of maintaining overall wellbeing. Research has...

Read More

The Benefits of Miso: Why It’s a Staple for Gut Health and How to Incorporate It into Your Diet

Fermented foods have long been prized for their digestive benefits, and few are as versatile...

Read More

Bone Broth for Gut Health: A Nutritional Breakdown

Bone broth has become a staple in many health-conscious diets, gaining widespread popularity for its...

Read More

Why Wagyu Beef Tallow is Essential for the Home Cook

This healthy fats supports the gut lining by reducing inflammation, which is crucial for maintaining...

Read More

Collagen - Essential for Gut health

Recently, there has been growing interest in collagen's important role in supporting gut health. This...

Read More

Choosing the Best Sauerkraut for Gut Health

If you’re looking to build your gut health, few foods can match the power of...

Read More

The Best Bone Broth for Gut Health, Immunity, and Vitality

Bone broth has been a staple in traditional diets for centuries, valued for its rich...

Read More

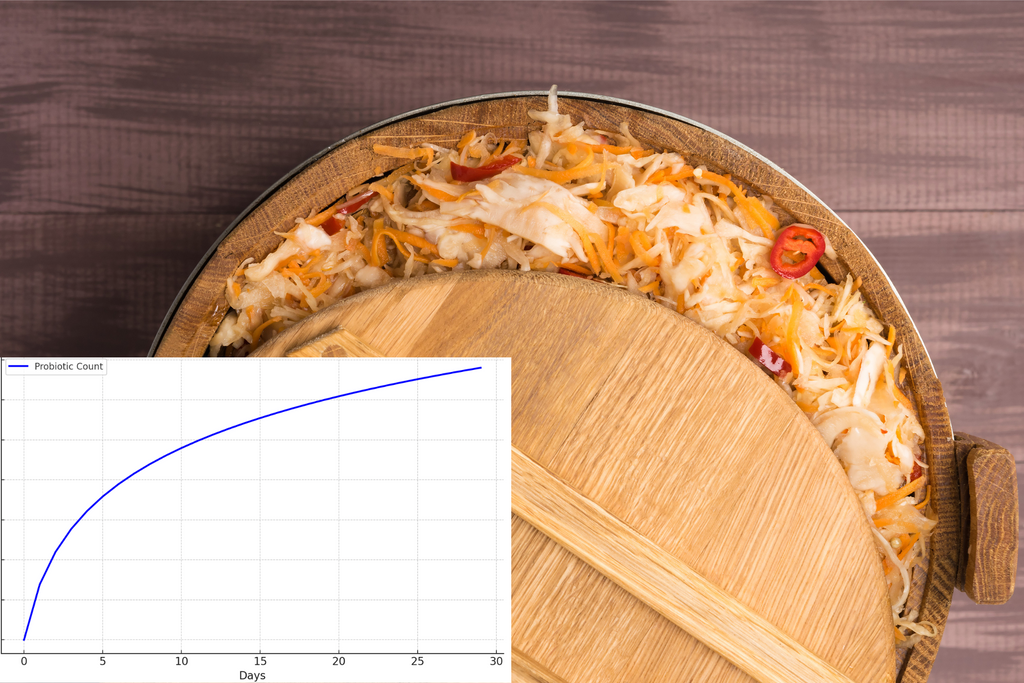

Why we Ferment in Oak Barrels

Aside from flavour, the other big reason people consume fermented foods like sauerkraut and kimchi...

Read More

The Power of Probiotic Juices

Probiotics are great, but probiotics in solid form (like probiotic capsules, pickles, olives, yoghurt and...

Read More

The Incredible Benefits of Miso: Why You Should Add It to Your Diet

Fungus is where Miso comes into its own, different sauerkraut or kimchi. During fermentation of miso beneficial...

Read More

Why We Long Ferment

We love fermented foods like Sauerkraut and Kimchi for many reasons including: probiotics, postbiotics, nutrient...

Read More

The Art of Making sauerkraut at Home

Sauerkraut isn't just delicious; it can make a huge difference to your health. Sauerkraut is...

Read More

Prebiotic vs Probiotic Food

Prebiotics and probiotics play vital roles in the process of bodily health. But what exactly...

Read More

Why Cauliflower Kimchi is Extra Beneficial (and expensive to make)

Cauliflower Kimchi has a more diverse array of prebotiocs, probiotics and postbiotics than any of our...

Read More

The Fatty Truth: Unveiling the Benefits of Saturated Fat in Tallow and Bone Broth Concentrate

Saturated fat has long been the subject of dietary debate, often cast as the villain...

Read More

The Role of Fermented Foods in Traditional and Modern Diets

For centuries, fermented foods have been a cornerstone of traditional diets.This spans across cultures and across time,...

Read More

The More, The Merrier: How People and Pets Enhance Your Microbiome Health

Food plays a massive role in the health of our microbiome, but it's not just...

Read More

Unlocking the Muscle Magic: How Probiotics Can Boost Your Strength

Are you constantly on the lookout for new ways to optimize your fitness routine? What...

Read More

Kimchi: A Fermented Superfood With Ancient Roots

Kimchi is widely known for its tasty, tangy flavour and spice, and it’s becoming more...

Read More

Exploring the Health Benefits of Bone Broth: A Gutsy Ferments Guide

One of the best reasons to eat bone broth, (aside from the fact that it tastes...

Read More

Why We No Longer Supply to Brick-and-Mortar Stores

For over a decade Gutsy has been supplying Kraut and Kimchi to stores all around...

Read More

Bone Broth powder vs Bone Broth Concentrate

Bone broth is becoming very popular due to its flavour and health benefits - especially benefits...

Read More

Oak Barrel Fermentation Vs Plastic Container Fermentation

Oak barrels have been used for thousands of years to ferment sauerkraut and kimchi, but...

Read More

Sauerkraut vs Probiotic Capsules for Gut Health

Gut health is important, but in our busy lives it's hard to eat the fermented food...

Read More

Canned Sauerkraut vs. Raw Sauerkraut

What's the difference between Gutsy Sauerkraut and the canned/tinned, room-temperature-stable (doesn't need refrigeration) or imported (European)...

Read More

How to Feed Your Gut

An important consideration is the feeding of our microbiome. What do we need to feed...

Read More

How to Seed Your Gut

What do I eat to seed my gut? It's important to give our gut microbiome...

Read More

How to Seal your Gut

As important as our microbiome is, we first need to consider the home of our microbiome,...

Read More

How to Purify your Gut

Pathogenic and dysbiotic bacteria don’t sound great, and inside your gut, they’re not. Imagine these...

Read More

How to Build a Resilient Gut Microbiome - In Brief

Research shows that the makeup and diversity of the bacteria in our gut are vitally...

Read More

Using Fermented Food To Reset The Gut Microbiome

Fasting and fermented foods have become two of the most popular trends in health, food,...

Read More

The link between sauerkraut and Vitamin K

Research has uncovered the link between sauerkraut and the essential nutrient Vitamin K2.

Read More

Two Studies May Back The Advantages Of A Balanced Gut.

Previously, we’ve reported on a number of scientific breakthroughs that back the importance of having...

Read More

What’s behind the rise in interest in fermentation?

You may have noticed a big trend over the past few years. The rise in...

Read More

Will Adding Fermented Food Maximise A Balanced Diet?

Nutritionists and health professionals recommend we eat a balanced diet. But how is this defined?...

Read More

Why Is Tangy Sauerkraut A Superior Fermented Food?

Did you know the tanginess makes sauerkraut superior to other fermented food in other ways?...

Read More

Fermented Foods And The Low Carb Diet

In this article, we’ll look at the possible role that fermented foods such as sauerkraut...

Read More

The History And Health Benefits Of Kimchi

Long a favourite of Korean people, kimchi is taking on new popularity in Western cuisine....

Read More

Can Sauerkraut Help You Lose Weight?

How can eating fermented food /sauerkraut help you lose weight? Though it’s early days, there’s...

Read More

Children And Fermented Foods: How To Introduce Them To The Good Bugs

Your growing child will benefit from eating the right balanced diet, including fermented foods, to...

Read More

Probiotics And Prebiotics: The Close Relationship

One of the topics that will come up as you scour the many articles, blog...

Read More

Organic Sauerkraut Benefits: Your Key To Great Health With Fermented Food

Have you ever wondered about how organic sauerkraut and fermented food benefits stack up? In...

Read More

Can Fermented Foods Lower Stress?

Much of the world is now engulfed in an apparent second wave of the pandemic...

Read More

Pasteurised Vs Unpasteurised Sauerkraut: How Heating Destroys Good Bacteria

People ask us questions like “Why is raw sauerkraut better?” and “What’s the effect of...

Read More

Fermented Foods And Mental Health: What’s The Connection?

Our fast-paced lifestyles, fibre-poor Western diet of processed food, stress and poor dietary habits have...

Read More

The Link Between Good Gut Bugs And Fermented Products

The recent rise in popularity of probiotic-rich fermented food products has seen more people become...

Read More

Supplements Or Fermented Foods, Which Are Better Probiotic Sources?

Is consuming supplements or fermented foods the preferred way to consume probiotics? It’s an important...

Read More

Sauerkraut And Vitamin C: The Nourishing Benefits

Sauerkraut and fermented and probiotic food have become a byword for gut health-friendly probiotics. But...

Read More